Today is World Bipolar Awareness Day. It lands on March 30th each year to celebrate the birthday of Vincent Van Gogh — who was posthumously diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder. You may already be familiar with his whimsically entrancing “Starry Night” – but a lesser-known fact is that the painting captures the view from his room at the Saint Rémy de Provence’s psychiatric facility.

It was one of 150 paintings he completed during his one-year stay — some of which researchers have speculated were likely to have been painted during episodes of mania.

My sister, Rachel, owned a pair of socks with Starry Night printed on them.

I didn’t think much of it at the time. Growing up we attended a fine arts school together. Art was always around us, and starry night is a classic. But in retrospect I can’t help but wonder if her own bipolar diagnosis fused a connection between herself and Van Gogh. If his artistic hand was a reminder to her of the beauty that can unveil itself within or on the other side of our darkest moments. Or if the fact that his capturing of the stars, with so much brightness and grandeur, was symbolic of hope amidst darkness.

Or maybe she just liked the socks.

The National Institute of Mental Health defines Bipolar Disorder as “dramatic shifts in mood, energy, and activity levels that affect a person’s ability to carry out day-to-day tasks. These shifts in mood and energy levels are more severe than the normal ups and downs that are experienced by others.”

- Approximately 4 in 100 Americans experience bipolar disorder in their lives

- Around 25 – 60% of those diagnosed with bipolar attempt suicide at least once

- Between 4-15% of those diagnosed with bipolar disorder die by suicide

Note: Statistics are from the National Library of Medicine.

My intention with this piece is to shed light on bipolar disorder – to help demystify and destigmatize a largely misunderstood and mischaracterized condition.

I hope it provides a comforting, informative foundation to build from.

I hope it helps you identify other questions that may be helpful to ask and understand.

And I hope it makes a small difference in your life and the life of someone you love.

A note from me-to-you before you continue onward

The following sections contain an amalgamation of scientific readings, my Sister’s reflections, and my own observations. My caveat to you is that I am not personally diagnosed with bipolar.

What this means is that although the writing you will read below is highly informed, it is also limited by my arm’s length proximity, my interpretation of what my Sister shared with me, my Sister’s unique experience of bipolar, and my gap in not seeing her at some of her hardest moments.

But even just as an observer of it, bipolar disorder has left an indelible, undeniable, unerasable mark on my life. That is why this piece is so important for me to share.

It is also important for me to share, because a significant portion of what’s included below was what I learned after my Sister died by suicide. One of the most haunting regrets I now have, is knowing that I did not prioritize (nor understand the criticality of) learning the ins and outs of bipolar soon enough. I could have been better equipped to empathize, understand, and support. But I wasn’t.

But I also know that at the same time, I was scared.

And that we were barely keeping up.

We were chasing answers

While trying to outrun our collective fears,

Moving between emergency room and psychiatric ward visits,

Caught within the tornado of an inadequate healthcare system,

Aching with pain from watching my Sister ache with pain,

While simultaneously battling unrelenting stigma.

And that’s really the only reason we can live with it.

Because we used all our knowledge and all the tools that we had access to, at the time.

And because amidst the swings, her ability to fight meant that we were all afforded

So many beautiful moments, days, weeks, months, and years.

We were all fighting, together.

And we did a damn good job of it.

So here it is,

My learnings about Bipolar Disorder.

Whether this piece is an introduction

or a continuation of what you already know,

I hope it holds meaning for you.

Introduction to Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder is a mood disorder. It is characterized by extreme shifts in mood, energy, and behaviour. On one side: dramatic lows (or depression) that are “literally unbearable” and on the other: highs (or mania) that “burn with equally fierce intensity”. Either episode can last hours, weeks, or months, but between the episodes, someone with bipolar disorder can experience stable mood.

Mania is characterized by hyperactivity, heightened mood (euphoric or irritable), grandiosity, an inability to sleep (often multiple days in a row), and reckless behavior (like spending money or engaging in uncharacteristically risky behaviours). In the midst of a manic episode, my Sister astutely captured the experience of her racing thoughts, in her journal: “my mind is expiring before it is used”.

Depression is characterized by extremely low energy, activity, and self esteem, an inability to perform day-to-day tasks, and feelings of guilt and hopelessness that can lead to suicidal ideation.

Both the episodes themselves and the dramatic shift between them can be debilitating. The character Skye Millar from the show 13 Reasons Why delicately captures the intensity of the swing that can happen between the two moods “Like, the good moods, they could be amazing, but… I was like… dancing on the edge of a really high cliff and the fall was just really fucking hard and far.”

My Sister also reflected on the shift from mania (and psychosis) to depression:

“After a psychotic episode comes a phase that was quite honestly, worse for me. It is during psychosis that what they call the gray matter portion of your brain gets largely damaged. This portion is connected to focus, social skills, creativity, productivity, and many more things that are quintessential to our everyday lives. The only thing that heals it is sleep. The only thing that protects it is the medication. So, for the time being, I was left with this brain that was hard to work with, and a perspective that depleted each joy. It was in this time that I was strongly convinced I could no longer achieve happiness. … I was hopeless. I felt pathetic, I felt ashamed. And worst of all I questioned if life was even worth it anymore. I could do nothing but wait until things got better. (And they did).”

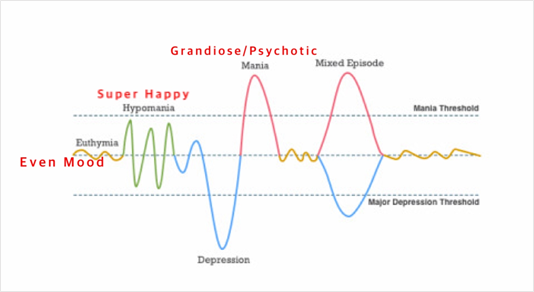

The best way to communicate the intricacies of Bipolar is through a diagram. The first diagram shows the different moods that can occur.

It is helpful to not look at this diagram “temporally”. That is, it is not demonstrating an individuals’ specific moods over time, but instead, the relative ranges that exist.

Euthymia is considered “steady” or “stable” state. This can be applicable for people with or without bipolar. It is important to recognize that any given person will experience ups and downs in their moods throughout their life, represented by the euthymia line. An important distinction with bipolar is that mood episodes are much, much more dramatic than what individuals without bipolar, experience.

In addition to Manic and Depressive episodes, the diagram highlights other important experiences of people with Bipolar Disorder:

- A hypomanic episode is similar to but less extreme than a manic episode.

- A mixed episode can contain symptoms from both manic and depressive episodes.

- A psychotic episode is a severe manic or depressive episode, involving hallucinations and/or delusions.

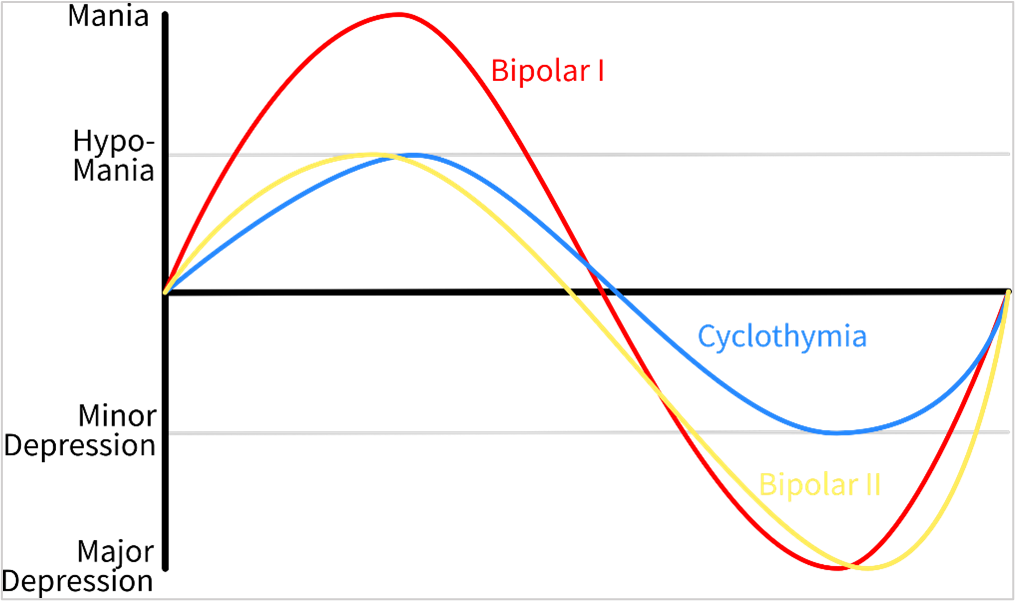

There are three types of Bipolar, shown in the diagram below:

The distinction between Bipolar I and Bipolar II is that both can experience major depressive episodes, but only Bipolar I experiences manic episodes. Cyclothymia is a less severe form of bipolar disorder.

“Rapid Cycling” can occur with any of these types – it is when the swings are quicker than “normal”. One threshold for this is four times a year, but Rapid Cycling can also be much more frequent than this.

My Sister, Rachel, was diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder I in 2014, her 12th grade year. She was diagnosed after a psychotic episode that was followed by a five month-long depression. In the span of time from 17 to 21 years of age she had 5 stays in psychiatric wards, due to three psychotic episodes.

Psychosis, Hallucinations, and Delusions

If someone is experiencing an extreme manic or depressive episode, it can result in Psychosis.

Psychosis

Psychosis is defined as “the loss of contact with reality in which the person cannot tell the difference between what is real and what is imagined” – and is more likely to occur in those with Bipolar Type 1. But what’s important to know is that psychosis does not typically surface as the “psychotic break” that our society has misunderstood and sensationalized it as. It is most often a slow, methodical build.

You may be more familiar with the symptoms of psychosis through awareness about Schizophrenia. Although the psychosis symptoms are largely the same between the two disorders, what differs is the timing. People with bipolar are “not supposed to experience psychosis outside of a mood episode” whereas those with Schizophrenia can experience symptoms outside of a mood episode.

Psychosis is predominantly recognized through two symptoms: hallucinations and delusions.

Hallucinations

Hallucinations can be auditory of visual. You can think of them like augmented reality – a layer of something un-real on top of reality.

Auditory hallucinations are voices or sounds that do not exist. The tricky part is that they are not typically “random voices” – instead, they are woven seamlessly into the middle of conversations or radio shows or tv shows, etc. My Sister and I worked hard to identify auditory hallucinations, together – if something in our conversation seemed “off” or incongruent, she would stop me mid-sentence and repeat what she heard to see if it was real. That was only possible because of how astute she was.

Rachel also shared some of her visual hallucinations with me, that were early signs of an oncoming psychotic episode: (1) when she would go for hikes, sometimes the tree trunks looked wavy and warped – as if she had entered Dr. Seuss’ world, and (2) when she would look at the floor or roof of a room she would sometimes see “acid patterns” – trippy mixes of colours and shapes. Visual hallucinations are different for everyone and could be anything: like a train engine moving full force beside you or the sun appearing as a missile coming toward you.

If you’ve dabbled in LSD, MDMA, ecstasy or another psychedelic or hallucinogenic drug, you may be familiar with a flavour of mania (and early psychosis). You may even be familiar with the intense paranoia and terror of a “bad trip”. These drugs are designed to give you a high from shifting your brain chemistry toward psychosis. For some people, this is fine in moderation. But for others (both pre-disposed and not pre-disposed to bipolar disorder) it can be the trigger that changes their life.

Delusions

Delusions are different than hallucinations. Delusions are when someone is seeing and experiencing the same world as the people around them, but their brain is telling them a distorted narrative of what they are experiencing. It can result in unimaginable terrors and further inability to trust one’s own brain. Although delusions can have similar themes from person-to-person, they are largely unique to an individual’s personal and environmental circumstances. Some of the “themes” of delusions include:

- Grandeur – when a person believes they are exceptional, extravagant, or famous.

- Jealousy – when a person believes their significant other is unfaithful and seeks evidence.

- Capgras – when a person believes their loved ones have been replaced by doubles.

- Persecutory – when a person believes they are being stalked, spied on, or conspired against.

Rachel sat with me one afternoon, sharing about her delusions. Had she not been brave enough to share, I would be at an astronomically larger knowledge deficit about what had happened. It provided answers to a set of questions that I am now privileged to have an answer to (among many that I don’t).

There were two pieces of information she shared that dramatically shifted my understanding of her circumstance – and provided me with at least some semblance of capacity to support her:

(1) My Sister’s most prominent delusions were persecutory.

They were frightening delusions of her world under attack: she was convinced that people were trying to harm and kill her. After hearing this, so many moments from the past years clicked into place. It finally made sense why she walked off the psychiatric ward one day to the local swimming pool. The threat she perceived to her life was an emergency. And growing up, our family had always said we’d meet at the pool if there were an emergency. She was doing exactly what she was taught to do. It was illogical to me at the time, but now, completely logical, given the narrative her brain was creating.

(2) In her delusions, all people around her were arbitrarily sorted into two buckets: Good and Bad.

In her delusions our Mom and Dad were sorted into the “Bad” bucket and myself and my husband were sorted into the “Good” bucket. Knowing this, it made sense, that at my wedding she needed me to sleep in the bed beside her to protect her. And it made sense, that she’d call me each day from the hospital, while not calling our Mom – one of her closest relationships outside of psychosis. This “sorting” complicated her care, especially when she turned 19. At 19, children become recognized as adults by the healthcare system. The intent of this is protection, but in this case, it made it difficult – her delusions convinced her to prohibit doctors from sharing information with our parents, to change the visitors’ list so their names weren’t on it, and to be released from the hospital without notification to our parents.

These pieces of information though, barely scratch the surface of what a psychotic episode can look like. There is no better person to explain the nuances of it, than a person who has experienced it.

Below you’ll find an excerpt from a piece that Rachel wrote, recounting the delusions and hallucinations she experienced in July 2018. She had started writing them down, with the intention that one day her lived experiences could help others.

The narrative begins as her and her boyfriend are heading downtown to see the fireworks:

“He offered me food. Smart Pop. This popcorn had been my favourite snack since middle school. I ate a bowl full, as well as a banana, then something strange happened.

He started reading my mind. Or rather, talking to me through mine.

I had experienced this telecommunication once before in my life, at Surrey Memorial Hospital. I sat in the emergency psych ward beside a woman who wouldn’t talk to anyone. She was telling me how to stay calm amidst the surrealness of discovering you can talk to people without words. I kept looking straight so that to anyone else it would look like we weren’t communicating. But when I stole a glance at her she looked at me knowingly. And it wasn’t just her that I talked to at this time, I reached out to friends.

I reached out to the lead member of my favourite musical group.

He told me that he was busy, too busy to talk.

When I discovered my boyfriend could read my mind I felt guilty. Had he known all my thoughts I’d wanted to hide from him? I looked at him and he stared sternly. He did know. But he told me it was fine. He was telling me to stay calm, that he had reached this level of mysticism some time ago.

And I was in danger.

Our location that we were headed to was his mom’s workplace downtown. I had never been before. His mom and sister gathered belongings, an immense amount of food and blankets for each of us.

“We might be there awhile,” they said.

“We have to get ready so we can leave as soon as the taxi gets here,” they said.

Again, the urgency.

I noticed that all the curtains had been drawn on the windows, they way it is in a lockdown, so that no one outside can see you.

I sat on the couch with my boyfriend. We didn’t talk. I watched as a spider crawled on the spot between the wall and the ceiling. I wondered if it was really there or if my mind was projecting it, like a hallucination. Then suddenly it was time to go.

Danger. Danger. Danger.

We entered the cab and his mom told the driver our destination, the sea bus at the Lonsdale Quay. At this point, I felt like someone was coming to my boyfriend’s house to kill me. Someone had gone crazy. Lost their mind, found a gun, and was coming to get me.

And of course, this person was a powerful magician. This person could not just read my mind from a far a way distance but could also see through my eyes. We were connected in this way.

So, I closed my eyes the whole taxi ride.

I didn’t want this person to see where we were on our drive and come to us.

When we arrived at the quay his mom didn’t pay for the cab. It had been provided by a company that protects and transports girls in danger. The cab driver was a police officer, the cab acting as an inconspicuous ghost car.

We got out. I had to go to the washroom. I felt funny as I walked into a McDonald’s, out of place. When I reached the restroom I could hear music, an odd song that I had never heard before.

It talked about an important time coming, then it hit me: this song was for me.

Something or someone is communicating to me in order to keep me safe.

I sat down and peed quickly, eager to get back to my boyfriend.”

Later that evening – once it became clear what was happening – my Sister and her boyfriend met myself and my husband at the hospital, where she was able to get medical support.

But what else can you do to help someone experiencing a delusion?

Start by listening. This can help you understand the nature and tone of the delusion. Then, avoid supporting or disputing any of the claims presented. Supporting claims can reinforce the delusion, whereas disputing claims can result in the individual believing them more (and they could think you are part of the “thing” or “group” that is intending to harm them). Instead, The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) recommends you validate and redirect their fears by “remaining calm and offering another way of looking at the situation, without insisting it is more rational”. An example, from NAMI:

If someone is experiencing a delusion, and points to houses along a block, saying: “those blinds are closed for a reason. It’s part of the investigation.”

It could be redirected to: “It’s interesting you see it that way, because I see it a little differently. I see that the sun is shining pretty intensely on those windows right now, so maybe the people have shut the blinds tightly to block out the sun.”

You can find more examples of this in practice, here.

Bipolar Disorder and the “Stress Cup”

Although the exact causes of bipolar disorder are unknown, The Black Dog Institute estimates that genetic factors play a role in 80% of people who develop bipolar disorder – making it the most likely psychiatric condition to be passed through families.

Similar to other disorders that can be inherited, just because someone is genetically predisposed to bipolar disorder (i.e., has genetic variations that have been passed through their family), does not mean that they will develop or “trigger” bipolar in their lifetime.

Why is this, though? The “diathesis-stress model of psychiatric illness [explains that] a genetic vulnerability to a disorder, blooms only if enough stressors cause those vulnerable genes to express themselves” (The Collected Schizophrenias, 2019). But what exactly does this mean?

In plain language: think of every human as having a “stress cup”.

As we experience environmental stressors in our lives – lack of sleep, life events like heartbreak or moving away to university, traumatic events like car crashes or losing a job, big celebrations, seasonal changes, using drugs – our “stress cup” fills up. And if too many of those stressors pile up at once, our “stress cup” overflows. For most people, this is okay. It may result in a tear-y set of days, feeling “overwhelmed” or similar. But for someone with a predisposition to bipolar, an overflowing cup can tip them into mania or depression – kick starting a bipolar cycle either for the first time, or as a repeat episode.

The challenge with bipolar is that there is no definitive recipe of stressors – no set concoction of “too much” to avoid. Once someone has had their first episode, they must test and learn how their mind reacts to each stressor, and the permutations and combinations of those stressors, too. All while attempting to manage (or avoid) other uncontrollable stressors in their lives. People living with bipolar must become expertly attuned to their bodies and minds.

I often think about my sister, my brother, and myself. All of us are genetically predisposed to bipolar. But my sister is the only one that diagnosable bipolar has surfaced in. So far.

It is said that most individuals predisposed to bipolar will experience an episode by their mid twenties. We’re both older than that now, but it does not negate the fact that there is still a chance – if myself or my brother have the genetic variations that can lead to bipolar – that it could still be triggered later in life. It’s the primary reason I stay away from drugs and the reason I must carefully consider the stressors I allow into my life (and how I respond to the uncontrollable ones that surface along the way). It’s also the reason that having children makes me hesitate, since the experience of child birth is one of the better-known “stressors” that can trigger psychosis.

But, in another family we know, three of five children are diagnosed with bipolar.

So, why just one of us, and not the others?

Were mine, my brother’s, and my sister’s stressors that different? Or maybe our “stress cups” were a different size? Or maybe similar stressors filled our cup in different ways?

Most likely, it’s the result of our individual genetic variations.

But the scientists don’t even know yet. There is no single gene that points to bipolar, and the genetic inheritance pattern for bipolar is still unclear. So, it’s likely that we may never really know, either.

Diagnosis and Learning to Live with Bipolar Disorder

Diagnoses are human constructs we’ve developed to sort ailments into treatable categories. This is easily applied and incredibly powerful with certain maladies – a broken leg, a heart attack, a stroke, diabetes, thyroidism – that have a singular genetic test, blood test, x-ray scan, or similar that can confirm the ailment. But with psychiatric disorders, the fact that there is no definitive test for diagnosis results inheated discussion around the extent to which diagnosis is helpful.

Psychiatric disorders are diagnosed based on an individual’s symptoms in combination with clinical judgement. These symptoms may be self-reported, reported by a loved one, or observed by a Doctor. This leaves room for interpretation and for a mismatch in words vs. feelings, which leads to imprecision. Think about the last time you tried to explain pain to a Doctor. Could you find the right words? Our retrieval set of descriptors are both limited and skewed by our biases and previous experiences.

There are also many categories of psychiatric disorders that have overlapping symptoms. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) was created by the American Psychiatric Association to define guidelines for diagnosing psychiatric disorders – i.e., it provides a checklist of symptoms. Think: “a pattern of two or more of A / B / C / D means you have X”. The lines between one disorder and the next are blurry and coupling this with self-reporting makes it even more difficult. This blurriness, the requirement for clinical judgment, and the reality that a clinical diagnosis will follow an individual through many facets of their lives (think: self-image, medical records, and treatment by family and friends, to name a few) means that Doctors will often refrain from diagnosing certain disorders. The intent of this is patient protection (from stigmas as well as an incorrect diagnosis) but the impact can be that a patient may be instead diagnosed with a “less stigmatized” disorder, which can lead to a treatment plan that doesn’t quite fit their needs.

To combat the negative discourse, there’s a passage from Esme Weijun Wang’s The Collected Schizophrenias which communicates the power of a diagnosis:

“Some people dislike diagnoses, disagreeably calling them boxes and labels, but I’ve always found comfort in pre-existing conditions; I like to know that I’m not pioneering an inexplicable experience … A diagnosis is comforting because it provides a framework – a community, a lineage – and, if luck is afoot, a treatment or cure. A diagnosis says that I am crazy, but in a particular way: one that has been experienced and recorded, not just in modern times, but also by the Ancient Egyptians.”

A diagnosis can be helpful in that it provides direction – or as Esme writes, a “framework” – in the form of suggested types of treatment. But there is not a one-size-fits-all (or most) solution for psychiatric conditions. For this reason,some people refer to them as “snowflake” or “fingerprint” conditions.

Rachel was diagnosed with Bipolar Type 1 in her Grade 12 year after her first manic episode.

I don’t know how she felt about diagnosis more generally. She held her diagnosis closely, but she also wasn’t particularly reserved about sharing it. If someone was genuinely curious and demonstrating kindness in their intent, she would tell them what she knew. She wanted her experience to help others.

One of the most comforting parallels that a Doctor shared with us two years after Rachel’s diagnosis was to think of Bipolar Disorder like diabetes. Similar to diabetes, Bipolar Disorder is not degenerative, but in most people, once it is triggered it does not go away. It is a condition which must be – and is entirely possible to be – managed throughout one’s lifetime. It is a condition, not a death sentence.

But because the manifestation of Bipolar is so unique to the individual (i.e., a “snowflake”), there is no silver bullet for managing it; no insulin equivalent. It requires a unique mix of management techniques, most notably medication, therapy, and mental hygiene:

- Medication: This can include antipsychotics (to help manage delusions and hallucinations), antidepressants (to relieve depressive symptoms), and/or mood stabilizers (to help manage extreme changes in moods). There are many types with effectiveness and side effects that manifest with different intensities based on the individual and the dosage. In some cases, an individual may need medication to stabilize after an episode and can then wean off. In other cases, an individual may need or choose to use medication for their entire life. There are different schools of thought around medication – but really, it is a personal decision.

- Therapy: This could include several different types or formats of psychological therapy (i.e., “talk therapy”) including psychotherapy, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), or counselling. Beyond providing a support network that helps reduce anxiety and manage stress, the purpose of therapy is typically to understand delusions, identify triggers, create a well-being plan, and identify early warning signs.

- Mental Hygiene: This is related to the “stress cup”. Once an individual understands their triggers, managing these triggers can be referred to as mental hygiene. Most commonly it is related to the need to monitor one’s sleep, alcohol consumption, hormonal changes, exposure to excitable (or traumatic) life events, nutrition, and schedule stability, to name a few.

Finding the right “mix” of these management techniques is where it can get cumbersome and exhausting. The only way to figure it out is through trial-and-error, which can be tedious and often impacts other aspects of an individual’s life: their job, their relationships, their love for themself. For some, it can take years of close self-examination, with the right support network, to pin it down.

But once an individual finds the right mix, and learns to manage it effectively, they can live their lives with normalcy. There are many, many individuals who live full, abundant lives with bipolar disorder.

The process of identifying one’s unique management of bipolar

also makes me think of words that Van Gogh wrote – maybe even as a reminder to himself:

“The beginning is perhaps more difficult than anything else,

but keep heart, it will turn out all right.”

Afterword

One of the hardest parts about a loved one dying is that when they are no longer around, there are so many questions you never even realized you wanted the answer to. Small ones. Trivial ones. Big ones. All of them. We can spend hours and years speculating, trying to believe we knew our “person” enough to have predicted what they would have said. But then doubt creeps in. Maybe you didn’t know them.

Or maybe you are ascribing meaning to the meaningless.

It’s a spiral I try to stay away from.

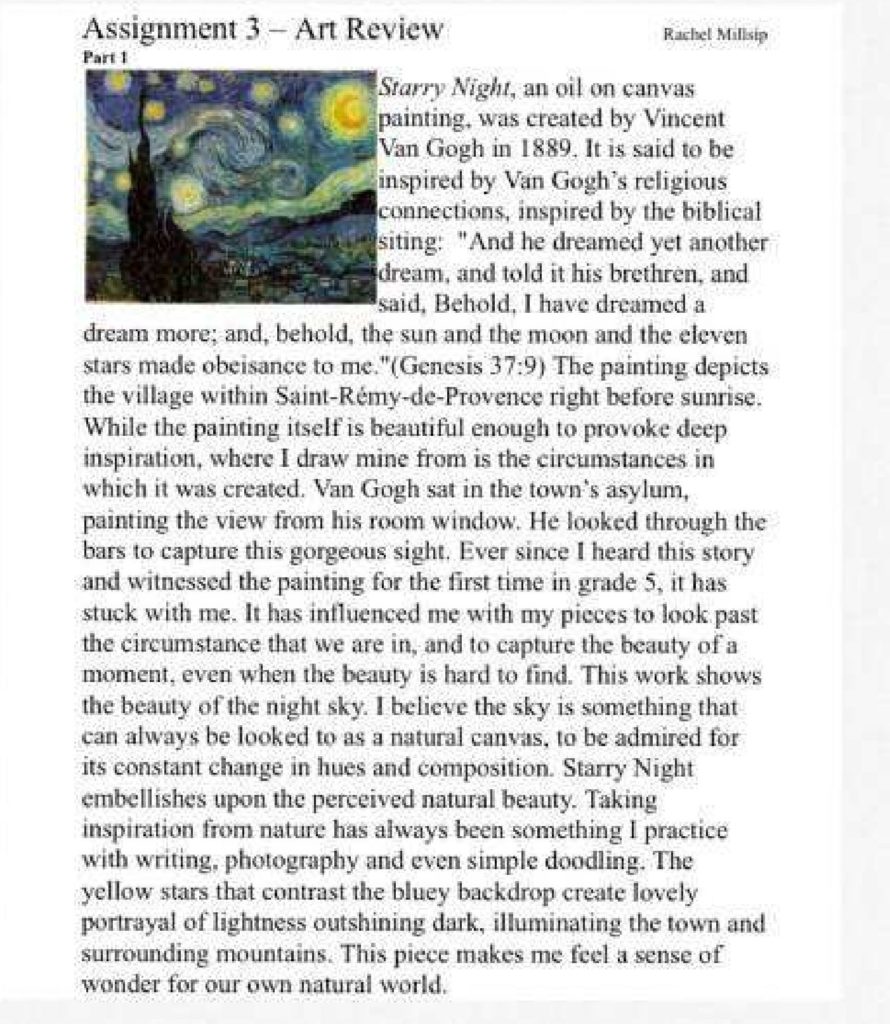

But as I was finishing up this piece, sifting through my Sister’s writing for the pieces that made sense to share, I came across this Art Review she wrote in her Grade 12 year, after her first psychotic episode.

And as I read it, between teary eyes and my big wide smile, it gave me an answer to a question that I thought I’d never have the answer to. And I don’t know if there is a greater gift in life than that.

Just as I had imagined, they were so much more than a pretty pair of socks.

Learn more about bipolar disorder:

Modern Love, Episode 3 – Take Me As I Am, Whoever I Am: Modern Love (TV Series 2019– ) – IMDb

The Black Dog Institute – A Detailed Guide on Understanding Bipolar Disorder: https://www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/resources-support/bipolar-disorder/

The Collected Schizophrenias – A collection of essays by Esme Weijun Wang: Collected Schizophrenias: Essays, Book by Esmé Weijun Wang (Paperback) | www.chapters.indigo.ca

Continue Reading My Collection of Grief Reflections:

- Surviving The Loss of Sisterhood

- (SOMETIMES) | Our Matching Tattoos

- I Wear My Dead Sister’s Clothes

- My Cherry Blossom

- Dear Autumn

- Behind The Scenes

- What Are You Thankful For

- Little Women

- Our Last Day Together

- Scrabble On The Psychiatric Ward

- What’s Harder? Death Days Or Birth Days?

- Rebuilding Trust With The World

- Christmas Eve

- Maddie, I Wish I Could Run Like You

- All We Can Do Is Try

- What To Say To Someone Who Is Grieving